Summary: The wealthy are constructing fortified bunkers, a silent acknowledgment of systemic vulnerabilities that remain opaque to most.

This essay examines the striking similarities between Japan’s speculative bubble of the 1980s and the current U.S. Nasdaq boom, arguing that both are fragile constructs sustained by three critical flaws: unsettled financial obligations, stock-based compensation, and questionable accounting practices.

By analyzing these parallels through a systems lens, this paper illuminates why the Nasdaq’s apparent strength may be illusory and why addressing this fragility is a formidable challenge.

Japan’s 1980s Bubble: A Mirage of Prosperity

The Japanese economic “miracle” of the 1980s was less a triumph of innovation than a product of speculative excess, driven by unique accounting practices. Unlike the U.S., which employs cost accounting, where assets are valued at the lower of cost or market value, with unrealized gains ignored—Japan adopted market value accounting. Under this system, increases in asset values were recorded as earnings, even without sales, creating an illusion of profitability.

Japanese corporations, particularly manufacturing giants, capitalized on this framework by investing heavily in Tokyo real estate. As property prices surged, firms marked up their balance sheets, reporting these unrealized gains as income. For example, a company holding a commercial property valued at ¥1 billion in 1980 might record a ¥500 million gain by 1987 if market prices rose, without selling the asset.

This practice fueled a feedback loop: rising asset values inflated corporate earnings, which attracted more investment, further driving up prices. At the bubble’s peak, Tokyo’s real estate was valued higher than the entire state of California, adjusted for inflation (approximately $5 trillion in 2025 dollars, per Nomura Research Institute estimates).

These gains, however, were largely theoretical. Unlike cash from product sales, real estate “earnings” existed only on paper, akin to unliquidated cryptocurrency holdings.

When the bubble burst in the early 1990s, Japan faced a prolonged economic stagnation, as firms grappled with overvalued assets and eroded balance sheets. This episode underscores how accounting practices can amplify speculative bubbles, a lesson critical to understanding today’s U.S. market.

The Nasdaq in 2025: A Modern Echo

The Nasdaq’s meteoric rise in 2025, driven by technology firms, mirrors Japan’s 1980s excesses in some ways, but is different in others. We will investigate this through 3 lenses:

- Unsettled trade obligations

- Stock-based compensation

- Questionable accounting practices.

Below, each is examined in detail, with comparisons to Japan’s experience and historical context to highlight systemic risks.

Unsettled Trade Obligations: A Global Debt Spiral

To understand the role of unsettled obligations, consider the Dutch trilateral trade of the 17th century, a system of disciplined financial settlement.

Dutch merchants engaged in a complex trade network, exchanging iron bars in Africa for enslaved individuals, who were then traded in South America for sugar, which was sold in Europe for tobacco or cotton.

Merchants borrowed guilders via trade notes, repayable by a fixed settlement date (typically two years). These notes, insured by banks, were rarely left unsettled, as non-payment risked severe penalties, including debtor prisons. Unsettled notes were traded as high-risk instruments and banned in Amsterdam to prevent speculative bubbles, ensuring systemic stability.

Contrast this with modern global trade. When Chinese firms export goods to the U.S., they receive payment in U.S. dollars, which cannot be freely used or repatriated due to China’s currency controls.

Instead, these dollars are invested in US Treasury securities—essentially IOUs from the U.S. government. Unlike Dutch trade notes, these Treasury notes are not settled; they are perpetually refinanced, with new debt issued to cover maturing obligations. In 2025, the U.S. national debt exceeds $35 trillion, with foreign holdings (including China’s) accounting for nearly 30% (U.S. Treasury Department, 2024).

This lack of settlement fuels inflation. From 1980 to 2025, the cost of feeding a family of four rose from $350 to $1,500, a 9.5% average annual inflation rate after compounding (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, adjusted). Similarly, housing costs increased 600%, and vehicle operating costs rose from 17 cents to 67 cents per mile (BLS and IRS data).

Unsettled Treasury obligations, unlike the barter-based Dutch system, create a persistent monetary overhang, eroding purchasing power and echoing Japan’s speculative excesses, where asset inflation masked underlying fragility.

Stock-Based Compensation: Inflating Wealth, Not Productivity

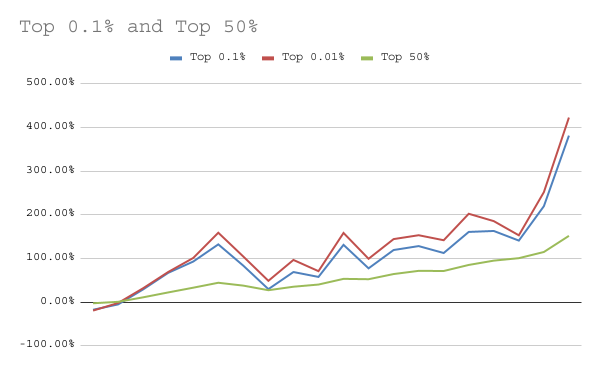

The distribution of income in the U.S. has grown increasingly unequal. Between 2002 and 2022, the top 0.1% of earners saw wage growth far outpace the top 50%, while the bottom 50% experienced negligible gains (IRS Statistics of Income, 2022). A significant driver of this disparity is stock-based compensation, particularly restricted stock units (RSUs), which dominate high-income compensation packages.

At Landon Fillmore, a tax advisory firm, client data reveals the prevalence of RSUs. For instance, a technology professional with an $820,000 W-2 income in 2024 had $650,000 in stock grants, netting $170,000 after taxes.

Even mid-level employees, such as a human resources manager earning $70,000, often receive $20,000 in RSUs.

Unlike cash wages, RSUs are taxed as ordinary income at grant, with companies selling a portion of the shares to cover tax liabilities (typically at 24% for incomes above $190,750 or 32% above $383,900 for married filers, per 2025 IRS brackets).

This process generates significant tax revenue—75% of federal income tax comes from the top 23% of earners, many reliant on stock-based income—but ties wealth to volatile equity markets.

This mirrors Japan’s bubble, where real estate gains inflated corporate earnings without tangible productivity. Stock grants inflate personal and corporate wealth without requiring cash outlays, freeing company funds for stock buybacks that further boost share prices. If the Nasdaq declines, these paper gains could evaporate, leaving high earners and the tax base vulnerable, much like Japan’s post-bubble corporations.

Questionable Accounting Practices: Obscuring Financial Health

Accounting practices in the U.S., while stricter than Japan’s market value system, still enable speculative distortions.

A key mechanism is stock buybacks, which tech firms use to manipulate financial metrics. Consider a hypothetical: a company grants shares to employees at $100 (recorded as compensation expense), then repurchases them at $300. This buyback is framed as “returning value to shareholders,” but it reduces ‘shareholders equity’—the portion of the balance sheet representing investor capital—by $200 per share. Unlike a traditional loss, which hits earnings, this loss is buried in equity accounts, obscuring its impact.

For example, ExxonMobil trades at $110 per share with $65 in shareholders’ equity, a reasonable premium. In contrast, Meta Platforms trades at $700 for the same $65 in equity, reflecting inflated valuations driven by buybacks and stock-based compensation (SEC filings, Q1 2025). These practices, while legal, erode the “quality of earnings,” a once-critical metric now rarely discussed.

In Japan, real estate markups similarly inflated earnings without cash flow; today, buybacks and RSUs create a parallel illusion of prosperity.

Moreover, stock-based compensation preserves corporate cash, enabling further buybacks or acquisitions. This cycle mimics Japan’s strategy of leveraging real estate loans to fund more purchases, concentrating risk in a single asset class—then property, now equities.

A Systems Perspective: Complexity and Fragility

As Donella Meadows articulated in systems theory, complex systems evolve through interconnected feedback loops, not isolated decisions. Japan’s bubble emerged from a confluence of accounting rules, speculative investment, and global capital flows, not a single policy or actor. Similarly, the Nasdaq’s rise reflects decades of monetary policy, technological innovation, and financial engineering, defying simplistic explanations.

Attempting to trace this evolution—like explaining the origins of a biological species—is fraught with uncertainty due to countless variables. Instead, we focus on the present state: a system where unsettled debts, stock-based wealth, and accounting maneuvers create a fragile equilibrium.

The Dutch trilateral trade, with its enforced settlement, offers a counterpoint, demonstrating how discipline can mitigate speculative risk. Today’s lack of such discipline amplifies systemic vulnerability.

Conclusion: Heeding the Bunker Builders

The bunkers of the ultra-wealthy signal an awareness of impending instability. Japan’s 1980s bubble, built on paper gains and speculative fervor, collapsed into decades of stagnation.

The Nasdaq, propped up by unsettled Treasury obligations, stock-based compensation, and accounting sleights of hand, risks a similar fate. These parallels reveal a truth: wealth, when divorced from tangible productivity, is fleeting.

Addressing this fragility requires confronting systemic flaws—enforcing debt settlement, reforming compensation structures, and demanding transparent accounting.

When natural systems become too rigid they collapse.

This collapse is either extinction or something close. A drop in Nasdaq would lead to a serious contraction of tax receipts on top of already absurd budget deficits. In addition, any cut in the US trade deficit would reduce the need for the “float” of US treasuries that circulate as unsettled trade notes.

The best way to understand this is a concept Zoltan Pozsar described as “exporting US dollar based balance sheets worldwide. This float is accounts payable and receivable on worldwide balance sheets which exist based on trust that trade will continue. This can be as much as 3 months of worldwide trade. It’s a staggering number.

The drop might be the cube root of the expansion in a shorter time horizon. The expansion of a sphere is 4/3 Pi R cubed. This was why the financial system could absorb tens of trillions in worldwide debt and not produce hyper inflation, until just recently.